The critical science supporting agriculture

Sydney Harbour Bridge during a huge dust storm September 23 2009. Photo by John Byrne

Agricultural chemicals have been in the news this year, but let's not forget the critical role they play in supporting modern agricultural production.

Australian farmers have long been recognised for the quality of their produce, but they are also among he most efficient, productive and environmentally sustainable in the world.

Indeed, a recent ABARES report comparing Australian agriculture to its major international competitors highlighted the nation's enviable record. It found our use of pesticides and fertilisers was among the lowest in the world, tillage practices were minimally disruptive to biodiversity, environmentally harmful subsidies were practically non-existent, and large swathes of land have been shifted out of agriculture and into conservation.

''Australian farmers are the best at producing high quality and value for money produce and doing it in the most environmentally sustainable way," CropLife Australia chief executive officer Matthew Cossey says.

"This is significantly underpinned by their access to safe, effective pesticides, which is - in this day and age - a really important issue, because we continue to see this disconnect between our urban-based consumers and their understanding of how the food, feed and fibre that's crucial to their life is produced."

Mr Cossey attributed the divide to a combination of 20th Century urbanisation and consumer complacency.

"Never before in human history have so many people relied on so few to produce their food," he says.

"In some ways, it's a bit of a double-edged sword. It's a testament to our farmers that Australian consumers don't have to worry about food (because) they know it's there.

"I don't think the Australian community recognise what amazing environmental leaps farmers have delivered at the same time as increasing production and delivering the best value, greatest variety of produce in our history."

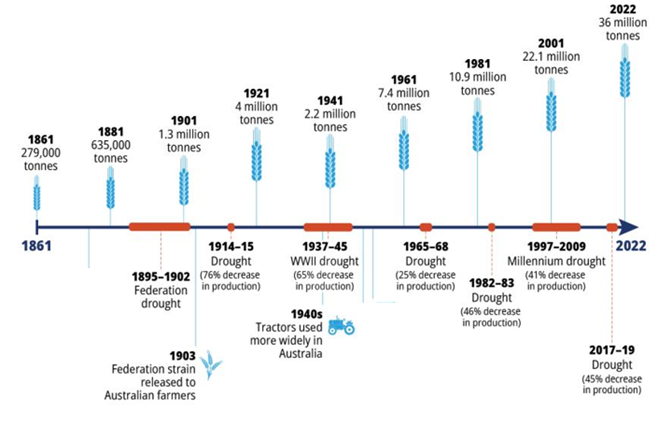

Historical timeline: Australian wheat production, 1861 to 2022 (Australian Bureau of Statistics)

FEEDING THE FUTURE

Mr Cossey says an estimated 135,000 farmers produced almost all the food consumed by Australia's 27 million people, and exported 65 per cent of their produce, making a significant contribution to the economy.

Leading the way was the grains sector, which increased wheat production 10-fold in the past century from 3.5 million tonnes in 1922 to 36.2 million tonnes in 2022 - more than 12 million tonnes of it produced by about 6560 farmers in NSW

The Australian Bureau of Statistics attributed at least some of that rise in production to "the ongoing development of chemicals to combat diseases, pests and weeds", and the breeding of higher-yielding, disease-resistant wheat varieties.

NSW Farmers Grains Committee chair Justin Everitt, who farms at Brocklesby in the Riverina, says access to a broad range of agricultural chemicals had also encouraged farmers to replace bare fallow with stubble retention and adopt practices like minimum tillage or no-till.

Using herbicides to manage weeds instead of cultivating the soil helped conserve soil moisture, prevent wind erosion and improve soil health by increasing organic matter.

"Every time you run a disc through the soil, you're taking moisture away," he says.

"And in a dry year, you are going to definitely impact yield and there will be a greater risk of dust storms."

Despite the shift from ploughing soil to applying herbicides for weed control - at a cost of $4.3 billion a year - chemical use in Australian agriculture was relatively low, according to the ABARES Insights report.

Pesticide application on cropping land was on par with Canada, but lower than the UK, US and many European countries, as well as being less than a quarter of that used in New Zealand.

New technology, such as camera-guided automatic spraying systems, was allowing farmers to spot spray paddocks instead of blanket spraying for weeds, which Mr Everitt says reduced chemical usage by as much as 85 per cent.

INDEPENDENT AND SCIENCE-BASED

Mr Cossey, whose organisation represents the crop protection and ag biotech industries, says innovation over the past 30 years had also resulted in better targeted chemicals containing much less of the active ingredient.

A report from Deloitte Access Economics, released in 2023, found $31.6 billion of broadacre and horticulture production was directly attributable to the judicious use of crop protection products in 2020-2021.

The third in a series commissioned by CropLife Australia, the report said this was a 53 per cent increase since 2015-2016.

By 2021-2022 there were 10,100 crop protection products registered with the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA), the independent statutory authority responsible for the regulation of agricultural chemicals in Australia.

The APVMA considered scientific information from a variety of sources when reviewing agvet chemicals to determine their safety, efficacy, and potential impact on trade. Product labels indicated the PPE and safe handling instructions required for their legal use, such as a closed loop transfer system, personal masks, filtered cabins for tractors, or directions for minimising spray drift.

"The reason the whole system works so well is it's underpinned by an independent and science-based regulator," Mr Cossey says.

"This reinforces effective use and safety of the products, both for those who are using it and for end consumers. We're very fortunate in Australia that farmers are supported by an independent, science based regulatory approach to access to these tools, as opposed to some of the bizarre, more ideological or political, non-scientific decisions we've seen made around the rest of the world."

Earlier this year, National Farmers' Federation chief executive officer Tony Mahar said timely access to world-leading agvet chemicals was critical to achieving Australian agriculture's ambition of $100 billion in farm gate output by 2030.

A farmer and his sons during a dust storm in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, April 1936. Photo by Arthur Rothstein/Library of Congress

DUST BUSTERS

Billowing clouds of thick reddish-brown dust from outback Australia frequently choked eastern Australia from 1895 to the early 2000s.

Caused in part by lengthy, severe droughts and large-scale land use change, the dust storms carried millions of tonnes of dust for hundreds of kilometres, in some cases as far as New Zealand.

In a 2016 paper, University of Sydney soil scientist Professor Stephen Cattle compared the history of severe wind erosion and dust storm activity in Australia with that of the famous US Dust Bowl states of Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico in the 1930s.

His research found evidence of similar rainfall deficits and extreme dust storm activity in the Western Division, which covered about 40 per cent of NSW, and the Victorian Mallee between 1895 and 1945.

During that period vegetation was cleared and cropping extended into drier, marginal areas typically more suited to grazing, at the behest of government departments, especially after World War I.

"Over-grazing of pastoral lands by sheep and rabbits further exposed the desiccated landscape to wind erosion," Prof Cattle wrote.

''At the peak of these intense episodes of wind erosion and dust storm activity, huge areas of pastoral and cropping land were abandoned as loss of topsoil and sand drift rendered these areas incapable of profitable production."

Between 1935 and 1945, Sydney experienced 10 long-distance dust events.

More recently, authorities described dust storms that enveloped Sydney in 2009 and 2018 as the worst in 70 years. Both followed severe drought.

Prof Cattle remembers dust storms from his childhood on the family farm at West Wyalong.

"That's partly why I developed an interest in dust storms and wind erosion and dust-derived soils, because I saw every Christmas time the window sills of our house were always covered in red dust," he tells The Farmer.

Prof Cattle attributed the declining frequency of dust storms in the past 50 years to more benign climatic conditions and the growing understanding by farmers of the importance of maintaining ground cover.

Adoption of no-till began in the 1960s and by 2014 it was estimated that 80 per cent of grain crops were produced using no-till and stubble retention.

But after three years of La Nina and a brief El Nino, Prof Cattle warned it was only a matter of time before dust storms occured again, especially with the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events under climate change.

"It's almost inevitable that we'll get some pretty drastic conditions again," he said.

"It might not be as crushingly severe because we know a bit more about the importance of keeping ground cover in place ... so if you can go into those periods with as much ground cover on the surface as possible, then obviously you're in a better place."

University of Sydney research volunteer Sophie Angelis sprays diluted wheatgerm oil over a plot to “hide” wheat seed from mice. Photo: Supplied

REDUCING SEED LOSS

Mice can be a major problem for grain producers, especially when they're present in large numbers at sowing. Conventional management relied on spreading baits made up of grain treated with zinc phosphide across the surface of freshly sown fields. The aim was to encourage mice to consume the bait and die before they could dig up newly sown seeds.

But researchers may have found a new less toxic way to reduce seed loss by interfering with the ability of mice to find food - using scents to distract and confuse them.

University of Sydney conservation scientist Professor Peter Banks said they had successfully used diluted wheatgerm oil to "hide" wheat seed from mice and stop pre-germination seed damage.

The method was tested on a 27ha wheat crop at Pleasant Hills during the 2021 plague when there were at least 300 mice per hectare at the site.

The mixture was sprayed over the surface of plots before, during and every two or three days after sowing until seedlings began to appear eight days later. The treatments reduced seed loss by more than 60 per cent.

"It worked because the mice, instead of digging in the ground to dig up the seed that was there, they just keep eating the spilled grain that's on the surface, because we made it hard for them to find where the sown seed was," Prof Banks says.

The USyd sensory conservation team also tested the concept - known as olfactory misinformation - on long-nosed bandicoots, which were eating and damaging black truffles at a farm near Braidwood, costing the owners tens of thousands of dollars.

In that case, they injected truffle oil into soil at points away from the truffle patch, and monitoring showed the native bandicoots learned there was no food reward to be had from digging at those spots.

"Then they stop showing up, and they don't go and dig up the truffles," Prof Banks says.

"That's the way that it's worked for them ... We've got a big box of new tricks and we think it's got a lot of potential."

In September, the team won a Eureka Prize in the environmental research category for their work, and Prof Banks said they would be working with the CSIRO in 2025 to look at ways to make the mouse research useful for farmers.

This article appeared in The Farmer magazine